Woodland Planning Guide

Overview

- there are many competing requirements for suitable land (in particular housing development)

- local councils often don’t own any land, so woodland development requires close cooperation with local landowners

- the subsidies available for woodland under the DEFRA Environmental Land Management System (ELMS) and the Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG) regulations are not mature

- woodland planning and Forestry Commission certification is complicated and requires expert support.

The Benefits of Woodland

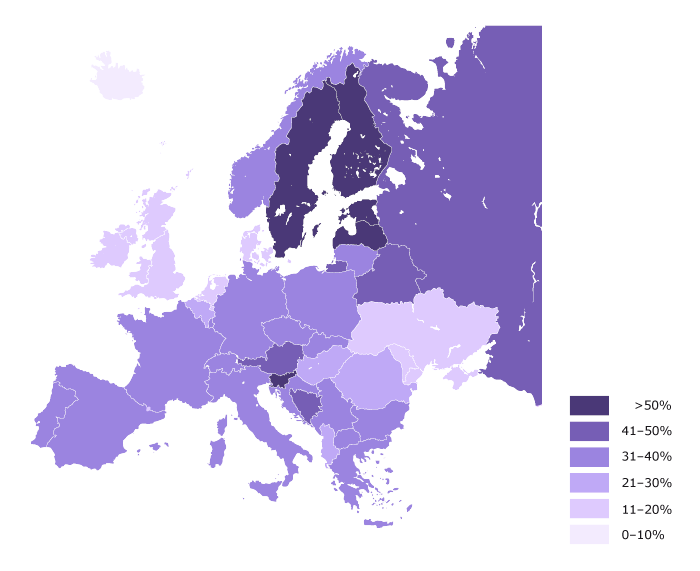

Area | Percentage Forest Cover |

UK | 13% |

Europe (EU) | 31% |

Europe (Total) | 46% |

World | 31% |

The main benefits of woodland are:

- Biodiversity: Woodland is one of the very best habitats to help

ecosystems to recover (provided it is planted and managed with this aim in mind).

Woodland does not suffer from the damaging effects of monoculture and the

extensive use of chemicals associated with agriculture.

- Carbon Storage and Sequestration: Mature

woodland provides an excellent carbon store (up to 1,400 tons of CO2

equivalent per hectare), and growing new woodland therefore offers the

opportunity to sequester carbon from the atmosphere and lock it away in the

wood and roots of trees. This allows councils to offset at least part of their

carbon emissions, which is an essential part of every Net Zero plan.

- Eco-system Services: Woodland supplies

many benefits in addition to carbon storage and biodiversity. These services

include the enrichment and stability of soil, flood prevention, improved air

quality and the provision of shade.

- Leisure and Well-Being: Woodland provides

an ideal environment for walking, horse-riding, and cycling. All these

activities promote health and well-being.

- Local Employment: Woodland generates

local employment, for instance in the planting and management of trees, the management

of leisure activities, and in wood-related industries.

- Using Timber to Replace Carbon Intensive Products:

Timber from woodland can be harvested and used to create sustainable products

and services which replace carbon-intensive alternatives, particularly for

building construction.

Strategic Considerations

Carbon Sequestration versus Carbon Storage

Mixed Benefits

It is important that a woodland is managed to deliver a mix of benefits (biodiversity, carbon sequestration, carbon storage, ecosystem services, leisure, local employment, and timber products). This mix will dictate the type and density of trees planted.Mixed Woodland

Mixed indigenous woodland is best for biodiversity, habitats and leisure. DEFRA therefore wants to encourage a mix of species, (with the mix depending on local conditions, including soil, flood risk, and habitats).Creating local employment

Woodland provides the potential for local employment,

especially once woodland is harvested for timber. The timber has to be cut,

transported, processed to create products (such as building panels), and finally

marketed and sold. All these activities can be outsourced or used to strengthen

the local economy.Timber Products in the Building Industry

The building construction industry is responsible for almost

40% of world-wide carbon emissions much of which is associated with the use of

cement, bricks and steel. Timber building construction therefore has huge scope

for reducing the carbon emissions associated with conventional construction

methods. Timber can be engineered to create building products which are strong,

safe and long lasting. These products are growing in popularity for use in small

and large buildings, and this trend is likely to accelerate as a powerful way

to fight climate change. The UK currently imports 80% of its timber for

construction, and so there is great scope for developing a domestic timber industry.

Mjøstårnet

(Trondheim) (280ft) is the world’s tallest wooden building

Developing and Implementing a Woodland Plan

We are working on a Woodland

Planning Guide for Parish Online which aims to provide data and advice for

councils which want to develop a proactive woodland plan. We expect to publish

this guide early next year, but some of the key datasets are already published

in Parish Online as described below:

Step 1: Existing Trees

Parish Online now contains a Friends of the Earth map of all the existing trees in Britain. This provides an excellent starting point for thinking about a woodland plan because it shows where trees can be planted to strengthen the vital connections between existing wooded areas.

Step 2: Woodland Opportunity Areas

Step 3: Map Planning Constraints

Step 4: Land Ownership Polygons

Step 5: Consider Optimum Woodland Schemes

- Woodland objectives from the point of view of biodiversity, carbon sequestration, carbon storage, eco-system services and the local economy

- The tree species best suited to the local soil, water and weather conditions

- The wishes of each landowner, which may not be in line with the wider area woodland objectives. For instance, at a council level the woodland scheme may favour a densely planted corridor of trees to connect two existing woodland areas to support wildlife. But this may not suit some of the affected landowners who have the absolute right not to take part in the scheme. So, the council and the landowners must work together to find compromises.

Step 6: Apply for grants and Forestry Commission Certification

Other Notes: Woodland Plans and Biodiversity Duty

Other Notes: Collaboration with the Principal Authority and other parties

Related Articles

Understanding the Property Density Map

Overview The Property Density Map is a piece of analysis produced by the Geoxphere team to help public sector organisations understand their local area better. By visualising how many residential properties there are in a hectare or square kilometre, ...Producing a map for a Planning Application

This tutorial relates to uses of Parish Online and XMAP within UK Local Government. Overview Local Councils may, on occasion, need to produce a Block Plan or a Location Plan as part of a planning application submission. This can be done in Parish ...IRENES Land Use Tool Data Documentation

1. Introduction This document describes the data sources, definitions and assumptions incorporated in the IRENES Land Use Tool (ILUT) available within the XMAP platform (https://irenes.xmap.cloud/login). It outlines the resources available for the ...Mapping Defibrillator Not-spots

Overview You can use Parish Online Mapping to plot the locations of defibrillators and share this information on your website using the Public Map facility (Using the Public Map). Once you've built up the map of existing locations, it might be useful ...Pre-defined Layers

Overview Parish Online has a range of layers pre-included in your account to make getting started with the software much easier. These are ready-to-use layers. Rather than having to create your own layer before you start drawing onto the map, you can ...